Urban gardens are a crucial resources in Philadelphia, particularly in Black and Brown neighborhoods. But many of these irreplaceable spaces are located on abandoned privately owned parcels that are tax delinquent–and these debts from previous absentee owners can put their land at risk of being lost at sheriff sale, often to low bids from land speculators, even if they’ve cared for the parcel for many years.

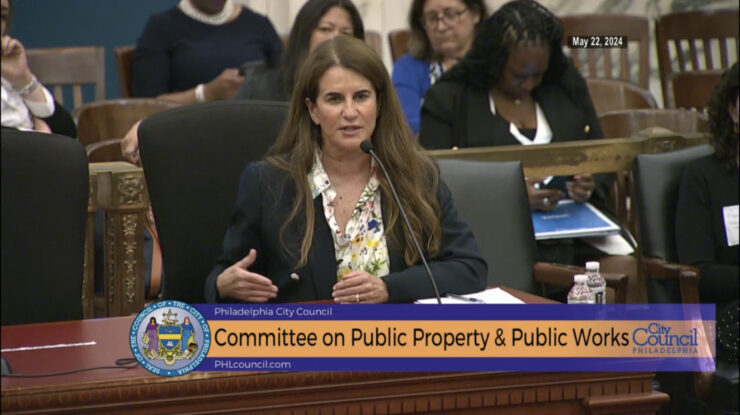

Our legal director Mimi McKenzie testified to Philadelphia City Council to support Bill 240187, which would allow the Land Bank under certain conditions to continue to be the sole bidder at these tax sales in order to ultimately transfer the gardens lots to their long-time stewards for a nominal fee.

Testimony to the Public Property and Public Works Committee in support of Bill 240187

May 22, 2024 – Good morning. I am Mimi McKenzie, the Legal Director at the Public Interest Law Center. For over 50 years the Law Center has been advancing the civil, social, and economic rights of communities in the Philadelphia region facing discrimination, inequality, and poverty.

Some folks are surprised that a civil rights organization that overturned Pennsylvania’s partisan gerrymandered congressional map in 2018 and recently had our system of public education funding declared unconstitutional also advances its mission by preserving community gardens and green space. But these spaces are critical anchors in Philadelphia’s Black and Brown neighborhoods. They are a place for residents to come together to grow fresh food, to seek shade and peace, and to gather and play. Peer reviewed studies back up what we intuitively all know to be true: urban gardens and green space have significant impacts on public health. They increase community access to fresh produce and improve neighbors’ mental and physical health. [1],[2],[3] They improve air quality, a critical function given that Philadelphia’s children have more than triple the rates of asthma compared to other children around the country. Cleaning and greening vacant properties results in significant reductions in gun violence and overall crime. [4] And gardens and green space help alleviate the impacts of climate change by creating cooling effects in blocks otherwise densely packed with concrete and buildings[5] and reducing flooding. [6]

But many of these vital gardens and green space are on land that is not secure. By that I mean that the neighborhood residents who are stewarding the land, in some cases for decades, do not have legal title to the land. Many of these gardens are on parcels that are privately owned and tax delinquent. That puts these gardens at risk of being lost at a tax foreclosure sale to developers or real estate speculators.

The Law Center provides pro bono legal representation to non-profit gardens seeking legal access to the land they have been maintaining. On occasion, we can quiet title for a garden client by filing a lawsuit against long-absent owners using adverse possession. For example, in 2018, our client New Jerusalem Laura, a nonprofit addiction treatment and recovery center in North Philadelphia run by two non-denominational nuns, was able to use adverse possession to obtain clear title to two vacant parcels it has been using for over two decades to grow food for its residents and the neighborhood children.[7] But many more organizations and communities doing similar work with excellent results are struggling to preserve their gardens because we are not able to meet the required threshold of twenty one continuous years of adverse, actual, exclusive, visible possession.[8]

“Many of these gardens are on parcels that are privately owned and tax delinquent. That puts these gardens at risk of being lost at a tax foreclosure sale to developers or real estate speculators.”

Here, the Land Bank plays a critical role, and it is why the Law Center collaborating with stakeholders actively sought and supported the creation of the Land Bank in 2013. The Land Bank can acquire these tax-delinquent and long-abandoned properties at Sherriff’s Sale by using its priority bid power and then return these parcels to productive use. Ordinarily, tax-delinquent parcels are sold at Sherrif’s Sale to the highest bidder. In lower income neighborhoods, these parcels often have low minimum bids and are attractive to speculators who after obtaining the parcel make no investment in maintenance, fail to pay taxes, and perpetuate the cycle of delinquency. Bill No 240187 ensures that the Land Bank will continue to be able to use its priority bid to exercise its right under certain conditions to be the sole bidder at these tax sales and break this cycle.

As you are aware, recently the City made a substantial financial investment to ensure that 90 garden parcels in primarily Black and Brown neighborhoods will be protected from Sheriff Sale by clearing liens held by U.S. Bank on tax delinquent, privately held properties. Now we need to ensure that the Land Bank, the Administration, and City Council can finish the job by foreclosing on these properties, having the Land Bank exercise its priority bid, clearing title, and ultimately transferring these parcels to their longtime stewards for nominal disposition fees.

Ensuring that the Land Bank can continue to use its priority bid is one important step. But just last Friday the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation released its 2023 annual report. There PHDC reported that since 2021 the Land Bank has moved forward with only twelve (12) garden dispositions. Currently there are 59 active applications for community gardens that have not gone to settlement. Like affordable housing, gardens and green space keep neighborhoods intact, equitable, and sustainable. Going forward the City must include the disposition of land for gardens and green space in its land use priorities consistent with the spirit and letter of the Philadelphia Land Bank Law we all worked so hard to enact.

Thank you for giving the Law Center the opportunity to testify today in support of Bill 240187 and in support of Philadelphia’s community gardens and green spaces.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8345884/

[2] https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13591-1

[3] https://www.sesync.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/Clarke%20et%20al.%20Urban%20Gardens.pdf

[4] https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1718503115

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6458494/

[6] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877705816330570

[7] Claudia Vargas, Will City Land Bank Save North Philly Nuns’ Community Garden?, The Phila. Inquirer (Apr. 2, 2018), available at https://www.philly.com/philly/news/politics/philadelphia-land-bank-medical-mission-sisters-community-garden-recovery-20180402.html.

[8] See Baylor v. Soska, 658 A.2d 743, 744 (citing Conneaut Lake Park, Inc. v. Klingensmith, 66 A.2d 828, 829 (Pa. 1949)); see also 42 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 5530(a)(1).