Testimony of Dan Urevick-Ackelsberg

Senior Attorney, Public Interest Law Center

March 5, 2024

Downingtown, PA–Chairman Bizzarro, Representative Friel Otten, and Members of the Policy Committee:

Along with my colleagues at the Public Interest Law Center, as well as co-counsel at the Education Law Center-PA and O’Melveny, it was my honor to represent the school districts, organizations, and families that brought Pennsylvania’s school funding litigation.

That decision established that the Pennsylvania Constitution “requires that every student receive a meaningful opportunity to succeed academically, socially, and civically, which requires that all students have access to a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary system of public education.” And the decision confirmed that the way we fund our schools fails this standard; that the Commonwealth’s elected leaders have “not fulfilled their obligations to all children under the Education Clause in violation of the rights of Petitioners.” To say it again: the Court’s judgment found the Commonwealth has failed its obligation to children.

Watch video of the hearing here.

The decision was not appealed, which means that “the Executive and Legislative branches of government and administrative agencies with expertise in the field of education, [have] the first opportunity, in conjunction with Petitioners, to devise a plan to address the constitutional deficiencies identified.” And the “plan devised by Respondents at the Court’s direction will have to provide all students in every district throughout Pennsylvania, not just Petitioners, with an adequately funded education.”

“This single-year appropriation should not obscure the broader task in front of you all: to enact a plan that charts out a year-by-year plan for full constitutional compliance. The time for single year budget fights must end.”

In response to the Court’s decision, the Governor, along with the Basic Education Funding Commission, has set out a seven-year plan to bring the school funding system into compliance. Over the long term, the proposal would mean dramatically improved conditions for our children, as students are provided the professionals and programs that can change the trajectory of their lives. [Footnote: The plan is not without faults—for example, seven years is a long time to wait for compliance, the facilities funding is too small, and Pre-K funding is basically nonexistent.]

This year’s appropriation would be a critical first step on the path to compliance. That said, the budget proposal you are considering only works because it is a downpayment, not a solution in isolation. This single-year appropriation should not obscure the broader task in front of you all: to enact a plan that charts out a year-by-year plan for full constitutional compliance. The time for single year budget fights must end.

I. A decision that sets out guideposts for a methodology

To understand the main components of the seven year adequacy and equity funding one also must take into account the foundations of the Court’s opinion. These include:

- “[E]very child can learn, regardless of individual circumstances, with the right resources.” This basic tenet was one “[a]ll witnesses agree[d]” to at trial.

- Pennsylvania is overly reliant upon local taxpayers, with low-wealth communities trying harder to raise funds for their schools relative to their means than high-wealth communities.

- When examining the appropriateness of funding, one must examine the relative need of the student body of the district.

- As a result of the funding system’s failures, many districts “lack the inputs that are essential elements of a thorough and efficient system of public education – adequate funding; courses, curricula, and other programs that prepare students to be college and career ready; sufficient, qualified, and effective staff; safe and adequate facilities; and modern, quality instrumentalities of learning.”

- In examining the constitutionality of the education system, one must consider how Pennsylvania students are actually faring. And there are widely unacceptable results on Pennsylvania’s own outcome measures—including the PSSA’s, Keystones, and graduation rates—which are indicative of a systemic failure.

- There is a cause and effect between that lack of resources and those outcomes: That “a funding system that is heavily dependent on local tax revenue,” which “does not adequately take into account student needs,” deprives students “access to the educational resources needed to prepare them to succeed academically, socially, or civically.”

II. The adequacy calculation

The proposal for adequacy fits hand-in-glove with the decision itself. It is a Pennsylvania model for success, based upon Pennsylvania’s assessments and graduation rates, Pennsylvania’s account of student need, and Pennsylvania’s actual spending data. These are the steps in the calculation:

- Use Pennsylvania’s performance standards to ascertain which districts are meeting state targets on PSSA’s/Keystones and High School Graduation. Pennsylvania sets targets for student performance on assessments and high school graduation, which the Commonwealth has said are achievable so long as additional resources are provided to students. The adequacy formula uses the 75 districts that are meeting those goals as models.

- Use Pennsylvania’s school funding formulas to calculate each district’s need (weighted student counts). Pennsylvania has already done the work of calculating student need, through the fair funding formula and special education funding formula. This adequacy formula uses those weights—poverty, English learner status, charter student stranded costs, and student disability status—as a district’s measure of need, calculating a weighted student count for each district. The only important change is that the calculation pairs actual in-school poverty data already used for federal and state reporting with Census data to better identify district-level poverty. [Footnote: For special education weights, the calculation uses weights from the Special Education Funding Commission.]

- Determine what those successful Pennsylvania schools spend per weighted student. The formula next calculates what those model districts are actually spending to achieve their results, relative to their needs. Here spending is defined as “current expenditures,” or what a district is spending on line 1000 (instruction, i.e., teachers), line 2000 (support, i.e., counselors and principals), and line 3000 (non-instruction, i.e., sports and extracurriculars) from district financial documents. It does not include lines 4000 or 5000 (facilities). And then it divides a district’s spending by its need (the weighted student count from step two), resulting in a spending per weighted student measure for each district.

- Eliminate high-spending outliers and take the median district. The formula then eliminates the highest-spending districts, including Lower Merion, New Hope, and Radnor, while leaving in the lowest spending districts. Then it uses the median spending of the remaining model districts: $13,704 per weighted student.

- Apply the successful schools’ adequate spending level as a target for all school districts. With all this in hand, funding targets for each district are straightforward: multiplying $13,704 against each district’s unique needs (that district’s individual weighted student count from step two). A district’s shortfall is its target minus what it is actually spending. Collectively, this results in an aggregate state shortfall of $5.4 billion. 387 districts have a shortfall, with a median shortfall of $2,950 per student among them.

- Determine the state share of funding. The final piece of the calculation is to determine what portion comes from the state. Given the core of the problem—a system overly reliant on local wealth—the formula requires the Commonwealth itself to raise the vast majority of needed funds. It does so by assuming, but not requiring, that each district will make an effort of at least the 33rd percentile of local effort. The end result is that the state share of the $5.4 billion shortfall is $5.1 billion, or 94%. Every district at the 33rd percentile or above would have their entire shortfall covered.

$5.1 billion in state funding would mean transformation for hundreds of communities across Pennsylvania, from Upper Darby and William Penn and Coatesville in the southeast, to every single district in Erie County in the northwest. It would mean more teachers, counselors, and tutors, updated curriculum, and up-to-date technology. It would allow school districts to implement the strategies that we all know work.

III. The tax equity calculation

The Governor’s proposal has one additional major source of funding: tax equity funding. This funding sounds complex but is rather straightforward. The formula identifies those districts making a local effort at or above the 66th percentile, examines the amount those districts are raising, and then allocates them funds that would effectively allow them to lower their taxes back down to the 66th percentile, with a wealth limitation for those districts with particularly high capacity.

“The task of bringing our public education system into compliance requires all of us to articulate a clear vision for the future. We cannot let another generation of children pass by before getting this right.”

This funding cannot be considered outside of the context of the broader adequacy calculation. And the first order of business for you all must be to set a path to adequate funding. However, if paired with a guarantee of adequate funding, it makes sense. As the Court noted, the Commonwealth’s lowest wealth districts actually make the highest tax efforts in the state. As a result, while still underfunded, districts like Pottstown and Coatesville are closer today to adequate funding than other Commonwealth districts, solely as a function of those communities taxing at far higher rates than most of the Commonwealth. This tax funding would undo some of that inequity, assisting those communities that have long been trying the hardest to fund their schools.

All told, there are 169 districts which qualify for $956 million in tax equity funding, including Pottstown and Coatesville, again spread over seven years. [Footnote: All this has limits: Even if the districts used their tax equity funding as a one-for-one to reduce taxes, they would still have a higher local effort rate than Downingtown at the conclusion of the seven year process.]

IV. Three different local districts

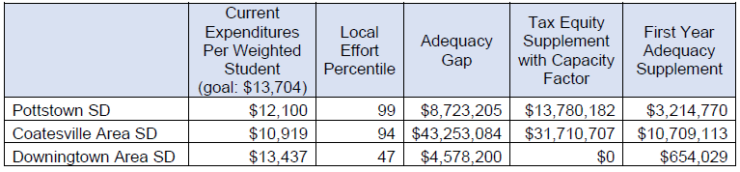

Downingtown, Coatesville, and Pottstown present an apt demonstration of how these calculations work in practice. Among the three, Downingtown spends the most relative to its need, and has only a small shortfall. It accomplishes this with an effort just below the state median. It therefore is eligible for $4.6 million dollars to reach adequacy over seven years. (Downingtown may still have needs; the calculation is a conservative one, which does not include things like facilities funding.)

Pottstown and Coatesville, on the other hand, have wide adequacy gaps, despite being two of the highest effort districts in the state. Accordingly, those districts are eligible for significant amounts of both adequacy and tax equity funding.

V. Other considerations in the Governor’s budget proposal

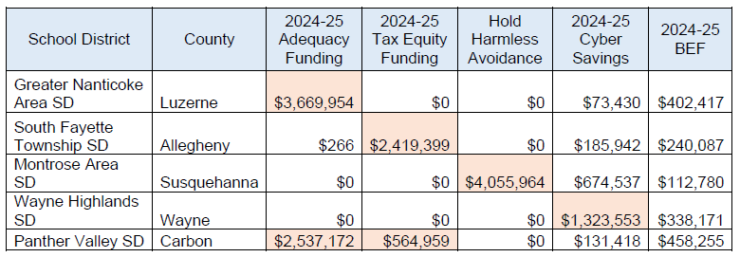

The adequacy and tax equity calculations are not the only ways school districts benefit from the Governor’s education proposal. For example, hundreds of districts benefit from the continued practice of hold harmless—which has effectively given some districts a head start towards adequacy. All districts receive savings from the Governor’s cyber charter reform proposal. And every district will receive an increase in basic education funding. Some examples include:

VI. Conclusion

The task of bringing our public education system into compliance requires all of us to articulate a clear vision for the future. We cannot let another generation of children pass by before getting this right. Instead, we need to make a down payment this year, and enact year-by-year legislation to end this injustice once and for all.