Staff attorney Dan Urevick-Ackelsberg presented testimony on fair funding for public education to the House Democratic Policy Committee on Tuesday, May 11, 2016.

Dan spoke to the needs of school districts across the state, the Commonwealth’s unconstitutional system of funding schools, and Philadelphia’s education situation.

Here is his testimony in full:

Dear Chairman Sturla, Representative Acosta, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for highlighting the issue of fair funding for public education. Nothing could be more important for legislators to address.

I would like to focus on three things in my testimony. The needs of school districts across the Commonwealth, the unconstitutional nature of our school funding system, and since we are in Philadelphia, the state of our own school district.

The Needs of School Districts across the State

As you know, as part of his 2015-2016 budget, Governor Wolf proposed an historic increase in education funds: an additional $400 million in basic education funding and $100 million in special education funding. In anticipation of that funding, school districts were asked to submit Funding Impact Plans, detailing how they would spend those funds. Over 96 percent of districts responded, with plans detailing the educational investments they would make. But, as you know, as a result of the budget stalemate, additional funds were only allocated deep into the school year, and even then, totaled approximately half of what the Governor proposed.

As we came through the budget stalemate and as another loomed on the horizon, we used a Right-to-Know request to gain access to those Funding Impact Plans. As you might guess, reading them a year later is quite sobering. There are two important, related takeaways from those Plans: just how basic those requests were, and how badly school districts in every corner of the state needed (and still need) increased funds.

How did school districts generally plan to spend this historic increase? On kindergarten teachers. On reading specialists. On librarians. And on books up to date with state standards. One school district reported it had not purchased a new reading series in twelve years. In other words, school districts were not making extravagant plans for that money. Rather, they planned to make investments towards the most basic of an educational program. We have sent our report on the Plans to leadership staff, but all of the raw data is on our website (http://www.www.pubintlaw.org/2015-impact-plans). I would encourage you to look at your own districts, to see how they fared, and how basic their requests were.

What is also clear from our report is that many school districts are still hurting from the 2011 budget cuts. Expenses go up every year, and districts that are near, or even below, their pre 2011 numbers, were simply trying to hold their heads above water. This was perfectly summarized by the Riverside School District, outside of Scranton, which said that “[w]e would love to provide STEM opportunities and Career Readiness opportunities, but would have to use the funding to support basic necessities for our district.” This sentiment was expressed over and over.

The Commonwealth’s Unconstitutional System of Funding Schools

How did we get to this point, where an historic funding increase would do no more than begin to pay for the basics? Because the state system of funding education is unconstitutionally broken in two related ways. First, many schools districts do not have the funds they need to adequately educate their students. This should come as no surprise to any of you, but it is worth reiterating that the legislature last studied how much it would cost to properly educate our students in 2007. At that point, schools were underfunded by $4.4 billion. While the state increased funds for the next three years, it is pretty clear that with the 2011 cuts and increased costs to school districts over the last eight years, that number is still in the billions.

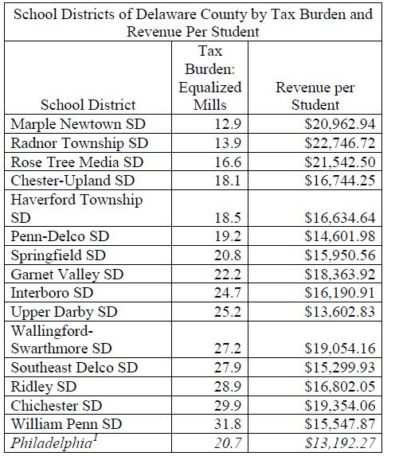

Second, vast inequities exist from district to district, with the educational opportunities children receive varying wildly depending on what side of school district border they live on. The school districts of Delaware County provide a vivid example of this problem:

As you see from the bottom of the chart, the William Penn School District, the lead plaintiff in our school funding litigation, has the highest tax rate in Delaware County, far higher than its wealthy neighbors. (The Commonwealth’s median tax rate is 17.7 equalized mills.) In other words, that district and those parents are doing everything they can to provide their children with adequate resources to succeed. Yet despite that tax rate—and with more students in poverty than its neighbors—William Penn has thousands of dollars less per student than the wealthier districts in the county. This matters: As a recent news report noted, in at least one classroom at a William Penn school, students rush to certain classes in the winter, so that they can get the best blankets in classrooms that are improperly heated.

As you see from the bottom of the chart, the William Penn School District, the lead plaintiff in our school funding litigation, has the highest tax rate in Delaware County, far higher than its wealthy neighbors. (The Commonwealth’s median tax rate is 17.7 equalized mills.) In other words, that district and those parents are doing everything they can to provide their children with adequate resources to succeed. Yet despite that tax rate—and with more students in poverty than its neighbors—William Penn has thousands of dollars less per student than the wealthier districts in the county. This matters: As a recent news report noted, in at least one classroom at a William Penn school, students rush to certain classes in the winter, so that they can get the best blankets in classrooms that are improperly heated.

1 Philadelphia’s numbers do not count $176 million in non-tax, local contributions in 2013-14, nor all of Philadelphia’s most recent tax increases. As a result, this is an understatement of the city’s efforts.

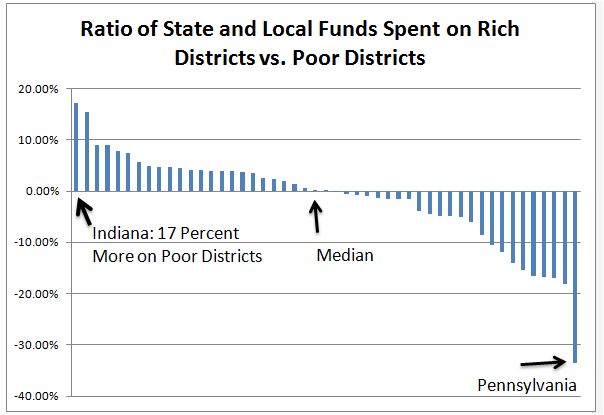

This system has left us, according to the federal government, as the most inequitable in the nation, spending 33 percent less state/local funds on our poorest districts versus our richest districts. As the below chart demonstrates, we are not just the most inequitable. Instead, we are close to as far from the next worst state as that state is from the median.

This inadequate, inequitable system leaves William Penn—and school districts all across the state—nowhere to turn. So if our students are ever going to be provided with the resources to provide children the education they deserve, the state must do more. And if we want to eliminate the accident of birthplace as the determining factor in the quality of a child’s education, we must end the vast disparities that exist from district to district.

In short, the Commonwealth must live up to its constitutional obligation to fund our schools.

A Philadelphia Story

But we are in Philadelphia, and so, it is useful to remember the dire straits of our Commonwealth’s largest school district. That district is run by the state, through a Commission that has five appointed members, appointed to their positions by a Mayor and Governor no longer in office, with “emergency” powers that have been dramatically curtailed by the Supreme Court, and which is in deep financial peril. And it is hostage to a charter school law that the Auditor General deemed the worst in the nation, which lets charter schools open while protecting them from sufficient consequences for the failure to educate children, and which creates a Hunger Games scenario, where each child that attends a charter school removes resources from a different child in a District school.

Philadelphia, despite its status as the poorest big city in America, also bore—and continues to bear—a disproportionate share of the 2011 cuts. Before 2011, Philadelphia received approximately 16% of state education funds. But because the 2011 cuts targeted programs that benefited poor districts like Philadelphia, Philadelphia absorbed about 37% of the cuts. Some of those cuts have been restored. But many of the cuts that Philadelphia particularly suffered from—programs like tutoring and charter reimbursements—have never been restored. Philadelphia’s share of the remaining cuts has therefore only grown. By our calculation, after the most recent budget, Philadelphia now shoulders 56% of the unrestored cuts.

And those cuts had real, meaningful, sustained impacts. Faced with a dramatic budget cut, the District closed neighborhood schools, cut thousands of jobs, eliminated gifted education in many schools, increased class sizes to unconscionable levels. And it did not just lose teachers. Instead, it laid off the counselors that help children get into college, the nurses that care for the sick, and the non-teaching assistants who keep peace in the halls. With our assistance, parents filed hundreds of complaints with the State Department of Education, alleging numerous deficiencies in schools. And for the first time in its history, the Department of Education found what we all knew to be true: curriculum deficiencies in multiple schools, as a direct result of those cuts.

Where are we today? With this reality: the School District of Philadelphia is underfunded by hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more than a billion dollars, each and every year. That underfunding is real, and felt by each child each day. Thus, we can argue about the priorities of the School District—and we as an organization frequently do so, through policy advocacy and litigation—but until we give Philadelphia children even close to what they need, we will be spinning our wheels, celebrating “victories” like the reintroduction of full time nurses in schools.

Finally, because I know there are City officials here testifying today, it is worth noting that the City must do more to fund our district, too. While the majority of our underfunding is caused by the Commonwealth, under any reasonable calculation, the City itself also needs to contribute more. The most recent such report was issued by former SRC Chair Wendell Pritchett, who noted that Philadelphia still appears to spend a smaller amount of its budget on education as compared to peer cities. In short, while the state has the most work ahead of it, we all need to do more.

I thank you for your attention to this crucial issue, and I am happy to answer any questions.